AEM-background

AEM-background.RmdThe Analytical Element Method

The analytical element method (AEM) represents the aquifer domain as the sum of analytical solutions of individual elements in the aquifer (Strack, 2017; Haitjema, 1995). The anem package focuses on 2-dimensional aquifers that reasonably adhere to the Depuit-Forschammer assumption, such that all flow lines are horizontal and parallel to the bottom of the aquifer (Strack et al., 2006). Generally, this requires that the lateral extent of the domain is much greater than the vertical thickness and elements within the aquifer span the entire depth of the water table. In other words, streams are fully penetrating and wells are screened from the bottom to the top of the saturated portion of the aquifer (Ferris et al., 1962). In practice, the assumption of 2D flow is typically adequate adequate when lateral distances are \(L>5\sqrt{k_v/k_h}b\), where \(b\) is the average saturated thickness of the aquifer, \(k_v\) is the vertical hydraulic conductivity, and \(k_h\) is the horizontal hydraulic conductivity (Haitjema, 2006). Vertical conductivity is often an order of magnitude smaller than the horizontal conductivity (Haitjema, 2006), in which case \(5\sqrt{k_v/k_h}\approx 1.6\).

Principle of superposition

Confined and unconfined aquifers can be treated as mathematically similar by strategically defining a state variable for hydraulic potential, \(\phi\). We set hydraulic potential proportional to \(\phi_c = z_0 h\) for confined aquifers, where \(z_0\) is the thickness of a confined aquifer and \(h\) is hydraulic head. In unconfined aquifers, we set hydraulic potential to \(\phi_u=h^2/2\), where the term \(h^2\) is discharge potential which is the square of the the saturated thickness of the water table, \(h\) (Strack, 2017). This allows us to write Darcy’s law as \(\mathbf{q} = -k \nabla \phi\) for both types of aquifers, where we now use \(k_h=k\) for the horizontal conductivity. In both cases, the groundwater continuity equation can be written as \[ \nabla^2 \phi = 0. \] Because this equation is linear in \(\phi\) it obeys the principle of superposition in which \(f(c_1 \phi_1 + c_2 \phi_2) = c_1 f(\phi_1) + c_2 f(\phi_2)\). This means that the cumulative effect of any number of groundwater components can be calculated as the sum of the effects from individual components, which can be calculated independently. In practice, it allows non-trivial groundwater dynamics to be represented by the sum of simple analytical equations.

Just as hydraulic potential obeys the principle of superposition, so do its derivatives such that the hydraulic gradient can be calculated as the sum of individual aquifer elements. Flow is then calculated from the gradient of hydraulic potential using Darcy’s law and keeping track of the definitions of \(\phi_c\) and \(\phi_u\). The average linear velocity is equal to \(v = q / n\), where \(q\) is the Darcy velocity, which is the volumetric flow per unit area (e.g., units of m/s), and \(n\) is porosity of the aquifer.

The primary task is then to set up the aquifer with individual elements representing important dynamics including pumping wells, boundaries, and recharge. The following sections describe how well pumping, aquifer boundaries, and recharge are represented in anem.

Pumping and injection wells

Wells are represented using a form of the Thiem solution describing steady-state hydraulic head in the vicinity (\(r \le R\)) of a pumping well (Thiem, 1906): \[ \phi - \phi_0 = -\frac{Q}{2 \pi k} \log \left( \frac{r}{R} \right)\,, \] where \(\phi\) is hydraulic potential at a distance \(r\) from a fully penetrating well that pumps at rate \(Q\) (positive for injection, negative for abstraction), \(R\) is the radius of influence of the pumping well, and \(\phi_0\) is the reference hydraulic potential when \(Q=0\). At distances \(r>R\), the hydraulic potential is undisturbed by pumping (\(\phi=\phi_0\)).

The radius of influence determines how far the cone of depression spreads from the well. The anem package implements multiple approaches to calculating the radius of influence, as described in Fileccia (2015). This includes the Cooper and Jacob (1946) approximation for confined aquifers, where the radius of influence is estimated as \(R=\sqrt{2.25 k z_0 t/S}\), where \(t\) is the elapsed time of pumping and \(S\) is the aquifer storativity. The package also includes the Aaravin and Numerov (1953) approximation for unconfined aquifers, where \(R=\sqrt{1.9 k b t/n}\). Although these approaches were defined for time-varying solutions, they can serve as an approximation for steady-state solutions by setting time to some long-term value.

Boundary conditions

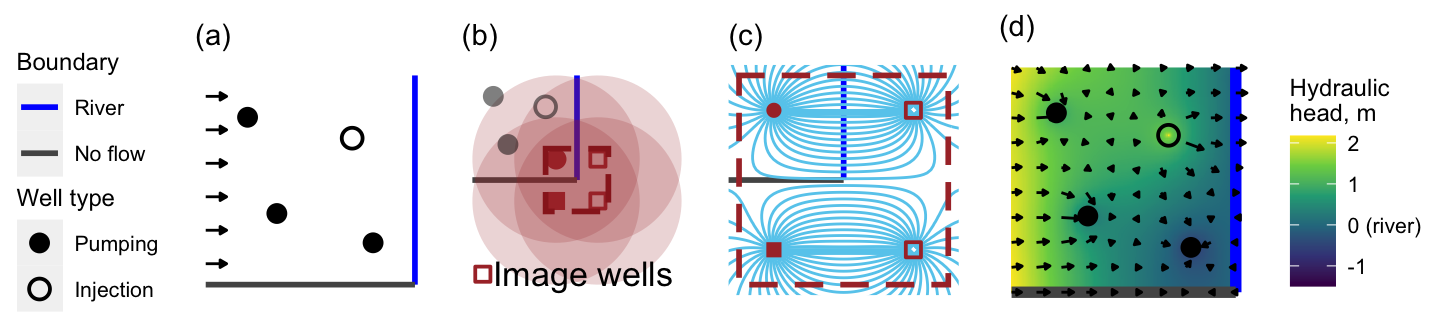

The effects of boundaries are realized through the method of images by strategic placement of virtual wells, or ``image’’ wells, that emulate the combined effect of actual wells and aquifer boundaries on the hydraulic potential surface (Freeze and Cherry, 1979). To demonstrate how this works, we use an example containing wells adjacent to a no-flow boundary, constant-head boundary, and in the presence of constant lateral flow towards the stream (Figure 1a). The image wells of the bottom right well (Figure 1a) are shown in Figure 1b, along with the radius of influence for each well. These wells mimic the behavior of the no-flow boundary, because two wells with equivalent pumping on opposite sides of the boundary create parallel flow lines along the boundary (Figure 1c, horizontal boundary). Two wells pumping at an equivalent rate but opposite sign mimic the effect of a constant head boundary (e.g., a river). In this case, the flow lines are perpendicular to the equal distance line meaning that no flow occurs along the boundary and it is of a constant head (Figure 1c, vertical boundary). This approach can be used to exactly reproduce no-flow and constant head boundaries for any number of wells.

Rectangular boundaries allow a straightforward implementation of the method of images, such that either side of a boundary can be a mirror image of the other side. For any two boundaries that are parallel, wells must be successively imaged across the opposite boundary until the distance of the next well image to the boundary is greater than the radius of influence. Irregular boundaries can be achieved using well images, but doing so requires solving systems of equations (Kuo et al., 1994) and is not implemented in the anem package.

Figure 1. (a) Aquifer scenario with four wells and arrows indicating constant background flow towards the river. (b) Well images and radii of influence for bottom-right well (red). (c) Reproduction of the no-flow and constant-head boundaries for single well using well images. (d) Hydraulic head and flow field for scenario. Note that the stream, flowing from top to bottom, switches from gaining to losing.

Recharge and background flow

Aquifer recharge can occur via a variety of mechanisms including those that directly result from wells (e.g., injection wells) and aquifer boundaries (e.g., recharge from streams to nearby abstraction wells). In the anem package, we also implement a type of recharge that creates a regional hydraulic head gradient, which in turn produces steady, uniform background flow. Such background flow can represent a variety of recharge scenarios. For instance, constant uniform flow could be generated from precipitation, after the aquifer reaches an equilibrium. As another example, flow could be driven by two parallel streams, with the higher-elevation stream recharging the aquifer which then discharges to the lower elevation stream. In some groundwater systems where the river is disconnected from the aquifer due to aquifer overdraft, the recharge from river could create a groundwater divide with flow in both directions away from the river.

The effect of constant lateral flow on hydraulic potential is calculated by integrating Darcy’s equation, which yields \[ \phi - \phi_1 = \frac{\mathbf{q}}{k}\cdot(\mathbf{x_1} - \mathbf{x}), \] where \(\mathbf{q}\) is the flow vector and \(\phi_1\) is a reference hydraulic potential at some location \(\mathbf{x_1}=\{x_1,y_1\}\). The flow vector \(\mathbf{q}\) is the lateral flux in units of [m/s], representing a volumetric recharge flow per unit length.

References

Aravin, V. and Numerov, S. 1953. Theory of motion of liquids and gases in undeformable porous media. Gostekhizdat, Moscow.

Cooper, H. and Jacob, C.E. 1946. A generalized graphical method for evaluating formation constants and summarizing well-field history. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 27, no. 4: 526–534.

Ferris, J., Knowles, D., Brown, R., and Stallman, R. 1962. Theory of aquifer tests. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1536-E.

Fileccia, A. 2015. Some simple procedures for the calculation of the influence radius and well head protection areas (theoretical approach and a field case for a water table aquifer in an alluvial plain). Acque Sotterranee-Italian Journal of Groundwater 4, no. 3.

Freeze, R.A. and Cherry, J.A. 1979. Groundwater. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Haitjema, H. 2006. The role of hand calculations in ground water flow modeling. Groundwater 44, no. 6: 786–791.

Haitjema, H.M. 1995. Analytic element modeling of groundwater flow. Elsevier.

Kuo, M.C.T., Wang, W.L., Lin, D.S., and Lin, C.C., and Chiang, C.J. 1994. An image-well method for predicting drawdown distribution in aquifers with irregularly shaped boundaries. Groundwater 35, no. 5: 794-804.

Strack, O., Barnes, R., and Verruijt, A. 2006. Vertically integrated flows, discharge potential, and the dupuit-forchheimer approximation. Groundwater 44, no. 1: 72–75.

Strack, O.D. 2017. Analytical groundwater mechanics. Cambridge University Press.

Thiem, G. 1906. Hydrologische methoden (hydrologic methods). Gebhardt, JM Leipzig, Germany.